As I wrote in an August Word Wednesday Post, I love the Olympic and Paralympic games. I love the way entire countries rise up behind their athletes and how small acts of kindness between athletes make you realize that even in the heat of competition, people are inclined to help one another. One of the things that drives me absolutely crazy about the Paralympic games though is the way they’re treated in the media and by the general public. During the Olympics, I couldn’t log on to Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook without seeing #Olympics or #Canada or one of the Olympic filters on a profile picture. During the Paralympics, however, I have had to actively look to find people mentioning the games. I understand that there is some degree of “sports fatigue” – in that a lot of people who aren’t necessarily into sports watch the Olympics but aren’t actually all that interested beyond their favourite sports. The 2 week wait between the Olympics end and the Paralympics begin also plays a role in diminished media attention and public appetite. What I vehemently disagree with is that the Paralympic games are in any way or shape less important than the Olympic games. Paralympians are elite athletes – period. If you think that just because someone is physically disabled, they aren’t training just as hard or just as athletically gifted as an able bodied athlete, I challenge you to go to the Canadian Paralympic Team’s Paratough website and try one of the Paralympian workouts. I tried the swimming core workout 4 days ago, and my abs haven’t forgiven me yet!

Before I get too far into this, I should address the question I’ve been asked quite a few times on social media – why aren’t there athletes with autism or other intellectual disabilities in the Paralympics? There’s no really quick answer, but the best I can come up with is this: They were part of the Paralympics in 1996, 1998, and 2000, which is when the wheels came off. Several athletes who competed in the intellectually disabled categories during the Sydney Paralympics were proven to have cheated the classification system and were not actually intellectually disabled at all – the International Sports Federation for Persons with Intellectual Disability, which had been formed to represent elite athletes with intellectual disabilities hadn’t been doing the background checks and documentation checks on all of the athletes which created a loophole that was exploited by dishonest paralympic committees. After the scandal in 2000, the Intellectual Disabled category was removed from all Paralympic competition with some integration brought back with very tight oversight for the 2008 Summer Paralympic games in Beijing China and there are ID (intellectually disabled) classes in several Paralympic sports. Still, the majority of intellectually disabled athletes compete in the Special Olympics World Games which happen in offset years to the Olympic and Paralympic games. The Special Olympics World Games are recognized by the International Olympic Committee as are the Deaflympics – which are actually older than the Paralympics and are exclusively for athletes with hearing impairments. The Deaflympics are distinct from the Paralympics and any other Para-sport organization because only members of the hearing impaired community can serve on the board for the The International Committee of Sports for the Deaf – who run the Deaflympics.

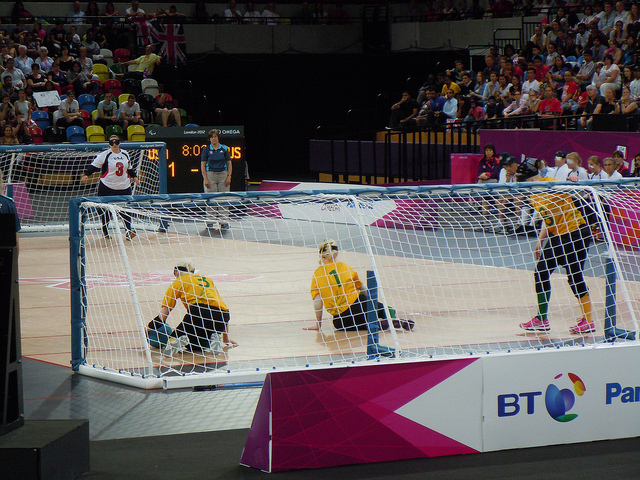

So, the Paralympics are primarily for athletes with physical disabilities including visual impairments. The visually impaired categories in para-sport are determined by degree of vision loss and in some disciplines the need for a guide, with one sport – goalball – being exclusively for visually impaired athletes. If you haven’t seen goalball you should try to watch one of the matches via the CBC Sports website – it’s really cool. The game is played in total silence so that the bells inside the ball can be heard by the players. Athletes with partial vision compete with completely blind athletes because all players wear eyeshades that block out vision. The court has tactile markings to help players orient themselves – the lines on the court are marked by lengths of twine that are then taped over. A goal is scored by throwing the ball using a bowling motion into the opposing net – while the opposing team attempts to block it of course. Goalball and Boccia are the two sports in the Paralympics that don’t have a Olympic counterpart. Boccia is a sport open to only physically disabled athletes with 4 classifications – 3 of which are for athletes with Cerebral Palsy. In Boccia, athletes throw coloured leather balls towards a white target ball (called a jack) on a long, narrow field of play that looks almost like a patch of grass but is smooth. The object is to be the closest to the jack after all 12 balls (6 per player or team) have been thrown. Boccia has been deemed to be similar to lawn bowling but I see it as more like lawn curling. I had a chance to try Boccia at a Para-sport day hosted by some local service organizations when I was younger. It was much harder than it looked, and I lost pretty soundly.

This week there has been a lot of media attention focused on the fact that the top 4 runners in the Men’s T13 1500m final all posted faster times than the Olympic Gold Medalist at that distance. The T13 classification is the highest level of functionality of visually impaired athletes so there were no prosthetic limbs or blades involved in the times. This was the one time I saw quite a few posts about the Paralympics, usually full of shock that Paralympians could run that fast. I replied to every comment with the same question – why should a visual impairment make an athlete run slower? I wasn’t surprised that these men ran faster than the Olympians – they are still elite athletes after all. I think Wendy-Ann Clarke of CBC hit the nail on the head when she reminded everyone that every race at the Olympics and Paralympics is different, especially at a distance like 1500m where strategy plays a big role in race management. The goal at the Olympics and Paralympics is to get a medal – records are secondary. So the athletes are going as fast as they need to to win, but not necessarily as fast as they possibly can. The gold medal winner at the Olympics, Matthew Centrowitz, controlled the race pace to one that gave him the biggest advantage – which was a slow first 2 laps and then a faster final lap – a tactic that would have forced his opponents to expend a lot of energy to try to pass him earlier in the race which would have drained their resources for later in the race when they needed to push. The T13 1500m final on the other hand had a racer, Bilel Hammami get off to a really fast start and the rest of the runners pushed to try to match it, resulting in a faster race overall. The assumption that para-athletes are somehow inferior to able bodied athletes has been bothering me for the past few days and is ultimately what inspired this post. Paralympians and Olympians are the top athletes in their sports; of course some amazing times will be posted during the Paralympic games, but the focus should be on the performance in and of itself. Comparing Paralympic times to Olympic times makes it seem like the Olympics are somehow better than the Paralympics when they’re not. The Olympics, Paralympics, Special Olympics World Games, and the Deaflympics are all the preeminent sporting events for the athletes competing. The difference is merely in who competes not in the athletic ability of the competitors.

All of this got me curious about the origin of the word Paralympic. The games were first contested in 1948 as the Stoke Mandeville Games named after the London treatment centre for spinal injuries. They were not officially named the Paralympics until 1988, but from 1960 on were informally called the Paralympics while formally known as the International Stoke Mandeville Games. The first games in 1948 were only for wheelchair athletes – and early literature refers to the games as the Paraplegic Olympics or Paralympics. As more categories of physical disabilities were added, the Para in Paralympics was assumed to be the Greek prefix meaning beside. So the Paralympics run alongside the Olympics. Now, the word Paralympics is recognized as a word in its own right, not as a portmanteau.

Paralympics ( Para·lym·pics) Plural Noun

- An international competition for physically disabled athletes, associated with and held following the Summer and Winter Olympic games.

Athletes – all athletes – are awesome examples of human strength and determination.

Great post.

I wish I had seen the runners. It would have been nice to see them flex their fast. 😉

Here you go https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j55N4ACT_1s 🙂

This is super informative. I did not know half of that info about intellectual disabilities. That really sucks that some people completely effed that up. People pretending to be disabled are all kinds of sad. I have enjoyed your coverage. I feel like someone should have paid you to go cover the Paralympics in person because you are the most informed person I know about this topic. Great post!

Thanks. I absolutely love watching sports of all types including Para-sport. The cheating controversy in Sydney was very unfortunate. The links I provided give more detail but suffice it to say, a few made it very hard for everyone else. In para-sport just like in non para-sport there are some people who will attempt to take the easy way out and cheat, whether it’s by faking a disability (or the severity of the disability) or by taking performance enhancing drugs. We have to try to weed them out to preserve the integrity of sport, but ensure we aren’t painting everyone with the same brush. I’d LOVE to cover the Paralympics one day. I saw a few events at the para-Pan-Ams last year and they were phenomenal!